ENGL513 Composition Theory & Pedagogy MONDAY UPDATES

|

Need to be in touch with me?

Lee Torda, PhD Interim Dean of Undergraduate Studies 200 Clement C. Maxwell Library 508.531.1790 Teaching Website: www.leetorda.com |

OFFICE HOURS: By appointment. Email me at ltorda@bridgew.edu with times/days you'd like to meet, and I will respond within 24 hours.

“Let’s save pessimism for better times” --Eduardo Galeano |

23 April 2024

Tuesday's class is on voice, style, and the dreaded grammar. What better way to end our semester--sort of where we started. It gets at the super complicated part of teaching writing. So much of the semester has been about the way freedom and literacy are connected-- Paolo Freire, the Brazilian Educator imprisoned for not teaching the colonizing language of Portuguese in Brazil, said that "one true word can change the world". And I really believe that.

I mean, despite everything, I totally believe that.

But I also know, and I said this in our very first class together, students aren't just writing in my class. They are writing in a lot of classes, classes where misspelled words matter and grammar and punctuation matter (even when the people grading the writing aren't super proficient at either). And so the oppressive and colonizing forces of SWE are always also at play. They simply can't be ignored. How do we balance a committment to student voice and authority in this environment? I don't have a neat answer. I'm seriously asking you.

In other news, not unrelated to our conversation is your own writing. Next week we will have an all class workshop. You don't have to read everyone's paper. Each student will be assigned two student papers to read. And I will read it as well. In-class, we'll have a discussion of each draft. It might seem weird, but hearing about other people's papers can be as useful as actually reading about them. I'm keeping the same workshopping groups as from last time, reposted here for your convenience:

Sara: Dawna & Kasey

Kasey: Cassie & Peyton

Peyton: Nick & Devon

Devon: Peyton & Nick

Nick: Kasey & Cassie

Cassie: Sara & Dawna

Dawna: Sara & Devon

To further facilitate this work, I'm asking you to post by the end of the week on our class discussion board, your answers to the following questions:

1. What are you trying to prove in your paper--what is your argument and how are you proving it?

2. What do you feel is working well in your paper and why?

3. What are you less confident about in your paper and why? What feedback can we give you that will help you to approach a final revision?

4. Are there things that you know you want or have to do in this draft but are not done yet that you think we should know about as we read?

Your answers to these questions will guide the workshop. So try to be as thoughtful and as complete as you can be.

AND ONE FINAL NOTE: Make sure you get your draft to your readers no later than Friday so that folks have time. Please know that your draft doesn't have to be totally finished, that's what that last question allows for. The more complete it is, the better the feedback you'll get, but don't let not being totally done prevent you from getting your draft to your colleagues.

16 April 2024

I'm not super thrilled with the reading I assigned for this evening. I think that Edlund and Griswold give a decent overview of older ideas about multilingual writers--the very fact that they call them "non-native speakers of English" should clue you in to that. But there has been a lot of interest in multilingual writers and writing, further shifting away from a deficit model of these writers in our classrooms. I wanted to put into writing some more recent ideas/theorists here. I'll talk a bit about this in class. I also want to say, that multilingual writing is not my forte or my field. I know the kind of generic stuff that people trained in my field know, but I don't know everything. If this is your interest, I will say that it's worth a deep dive into the field. Multilingual writing theory and pedagogy have evolved significantly in recent years, reflecting a growing recognition of the complexity and richness of writing practices among multilingual writers.

One key aspect of current multilingual writing theory is the recognition of writing as a dynamic and context-dependent practice shaped by various linguistic, cultural, and social factors (which fits with everything we've been reading in Adler-Kassner & Wardle). Scholars such as Suresh Canagarajah have argued for a "translingual approach" that views language boundaries as fluid and encourages writers to draw on their full linguistic repertoire in their writing. This approach challenges traditional monolingual norms and emphasizes the value of linguistic diversity in writing.

When I talk with my niece, who speaks Portuguese as her first language, with a better understanding of spoken English than I have of spoken Portuguese, we "translingual," as my husband puts it. I talk in English and she talks (slowly) in Portuguese and we use our phones and google-translate (because I'm a decent reader of Portuguese). And we have pretty robust conversations. At the end of a long day of this, however, both of us just want my husband and her uncle to translate for us. And sometimes, we both really, really misunderstand each other.

Another important aspect of multilingual writing theory is the concept of "code meshing," which refers to the mixing of linguistic codes (such as English and Spanish) in writing. This is not a new idea. People have been talking about code-switching for a long time, but code-meshing is a bit different. Scholars like Vershawn Ashanti Young have explored how code meshing can be a creative and strategic choice for multilingual writers, allowing them to convey complex ideas and identities that may not be easily expressed in a single language. Here's a for instance you might recognize. Do your students use "e" for "and"? In drafts, many of my Cape Verdean Creole- speaking and Spanish-speaking students do. It's automatic in both their writing and speaking. So much so that I don't even notice it when I'm reading their writing.

In terms of pedagogy, current approaches to teaching multilingual writers emphasize the importance of building on students' existing linguistic and cultural resources. Scholars such as Paul Kei Matsuda advocate for a "genre-based approach" that helps students understand the rhetorical conventions of different genres and cultures, empowering them to navigate diverse writing situations. This should resonate after last week's conversation. The idea of teaching genre explicitly instead of implicitly has value.

Critiques of current multilingual writing theory and pedagogy include concerns about essentializing language and cultural identities. Some scholars argue that approaches like the translingual approach run the risk of homogenizing diverse linguistic practices and overlooking the specificities of individual writers' experiences. There are also concerns about the practical challenges of implementing these approaches in the classroom, especially in contexts where standardized testing and monolingual ideologies dominate. Something I know all of you think about. All the time.

Tuesday's class is on voice, style, and the dreaded grammar. What better way to end our semester--sort of where we started. It gets at the super complicated part of teaching writing. So much of the semester has been about the way freedom and literacy are connected-- Paolo Freire, the Brazilian Educator imprisoned for not teaching the colonizing language of Portuguese in Brazil, said that "one true word can change the world". And I really believe that.

I mean, despite everything, I totally believe that.

But I also know, and I said this in our very first class together, students aren't just writing in my class. They are writing in a lot of classes, classes where misspelled words matter and grammar and punctuation matter (even when the people grading the writing aren't super proficient at either). And so the oppressive and colonizing forces of SWE are always also at play. They simply can't be ignored. How do we balance a committment to student voice and authority in this environment? I don't have a neat answer. I'm seriously asking you.

In other news, not unrelated to our conversation is your own writing. Next week we will have an all class workshop. You don't have to read everyone's paper. Each student will be assigned two student papers to read. And I will read it as well. In-class, we'll have a discussion of each draft. It might seem weird, but hearing about other people's papers can be as useful as actually reading about them. I'm keeping the same workshopping groups as from last time, reposted here for your convenience:

Sara: Dawna & Kasey

Kasey: Cassie & Peyton

Peyton: Nick & Devon

Devon: Peyton & Nick

Nick: Kasey & Cassie

Cassie: Sara & Dawna

Dawna: Sara & Devon

To further facilitate this work, I'm asking you to post by the end of the week on our class discussion board, your answers to the following questions:

1. What are you trying to prove in your paper--what is your argument and how are you proving it?

2. What do you feel is working well in your paper and why?

3. What are you less confident about in your paper and why? What feedback can we give you that will help you to approach a final revision?

4. Are there things that you know you want or have to do in this draft but are not done yet that you think we should know about as we read?

Your answers to these questions will guide the workshop. So try to be as thoughtful and as complete as you can be.

AND ONE FINAL NOTE: Make sure you get your draft to your readers no later than Friday so that folks have time. Please know that your draft doesn't have to be totally finished, that's what that last question allows for. The more complete it is, the better the feedback you'll get, but don't let not being totally done prevent you from getting your draft to your colleagues.

16 April 2024

I'm not super thrilled with the reading I assigned for this evening. I think that Edlund and Griswold give a decent overview of older ideas about multilingual writers--the very fact that they call them "non-native speakers of English" should clue you in to that. But there has been a lot of interest in multilingual writers and writing, further shifting away from a deficit model of these writers in our classrooms. I wanted to put into writing some more recent ideas/theorists here. I'll talk a bit about this in class. I also want to say, that multilingual writing is not my forte or my field. I know the kind of generic stuff that people trained in my field know, but I don't know everything. If this is your interest, I will say that it's worth a deep dive into the field. Multilingual writing theory and pedagogy have evolved significantly in recent years, reflecting a growing recognition of the complexity and richness of writing practices among multilingual writers.

One key aspect of current multilingual writing theory is the recognition of writing as a dynamic and context-dependent practice shaped by various linguistic, cultural, and social factors (which fits with everything we've been reading in Adler-Kassner & Wardle). Scholars such as Suresh Canagarajah have argued for a "translingual approach" that views language boundaries as fluid and encourages writers to draw on their full linguistic repertoire in their writing. This approach challenges traditional monolingual norms and emphasizes the value of linguistic diversity in writing.

When I talk with my niece, who speaks Portuguese as her first language, with a better understanding of spoken English than I have of spoken Portuguese, we "translingual," as my husband puts it. I talk in English and she talks (slowly) in Portuguese and we use our phones and google-translate (because I'm a decent reader of Portuguese). And we have pretty robust conversations. At the end of a long day of this, however, both of us just want my husband and her uncle to translate for us. And sometimes, we both really, really misunderstand each other.

Another important aspect of multilingual writing theory is the concept of "code meshing," which refers to the mixing of linguistic codes (such as English and Spanish) in writing. This is not a new idea. People have been talking about code-switching for a long time, but code-meshing is a bit different. Scholars like Vershawn Ashanti Young have explored how code meshing can be a creative and strategic choice for multilingual writers, allowing them to convey complex ideas and identities that may not be easily expressed in a single language. Here's a for instance you might recognize. Do your students use "e" for "and"? In drafts, many of my Cape Verdean Creole- speaking and Spanish-speaking students do. It's automatic in both their writing and speaking. So much so that I don't even notice it when I'm reading their writing.

In terms of pedagogy, current approaches to teaching multilingual writers emphasize the importance of building on students' existing linguistic and cultural resources. Scholars such as Paul Kei Matsuda advocate for a "genre-based approach" that helps students understand the rhetorical conventions of different genres and cultures, empowering them to navigate diverse writing situations. This should resonate after last week's conversation. The idea of teaching genre explicitly instead of implicitly has value.

Critiques of current multilingual writing theory and pedagogy include concerns about essentializing language and cultural identities. Some scholars argue that approaches like the translingual approach run the risk of homogenizing diverse linguistic practices and overlooking the specificities of individual writers' experiences. There are also concerns about the practical challenges of implementing these approaches in the classroom, especially in contexts where standardized testing and monolingual ideologies dominate. Something I know all of you think about. All the time.

9 April 2024

A few things: First, I failed to mention that the profile page with excerpts and links to your literacy histories have been available since last week. Meant to say that in class. I'm hoping to do a modest assignment with them in tonight's class, but am not sure we'll have time.

Second: Peyton and Sara have the floor tonight for their presentation. I opted to have that serve as our presentation over rhetoric and argumentation, but I will spend some time talking about that connection in class.

Third: For our workshop tonight, I'm hoping that folks can get more than one reader, so I've set up groups in a weird pattern of three so everyone has two readers. I know that the syllabus is confusing, but, essentially, I don't think we'll have time for folks to get all the feedback to each other that might be useful, so I'm hoping that folks will take the time to respond completely over the next few days. I say midnight on the day of class, but that's not realistic when we end nearly at 9:00. Perhaps get feedback to folks by Friday of this week, giving folks the weekend to get things done.

Sara: Dawna & Kasey

Kasey: Cassie & Peyton

Peyton: Nick & Devon

Devon: Peyton & Nick

Nick: Kasey & Cassie

Cassie: Sara & Dawna

Dawna: Sara & Devon

Lastly, last week most folks did not have any kind of a reading journal and the week before that, not many people had posted to our discussion board. Please try to catch up with that material as soon as you can. I am not very demanding about these things, but I do keep a record of these things and the last two weeks have some holes in them for many folks.

Questions for Tuesday night's workshop (I'll most likely cut and paste these into the comments--but if you need them for later for your own paper or one of the two papers you are reading):

1) What are your takeaways from reading their observations--are there things that you notice that your writer did not? Tell them. Tell them why they are interesting and how they might fit into the overall analysis?

2 Is the balance of analysis to observation appropriate? If not, where are they erring--too much observation and not enough of what it means? Too much analysis without enough observation to back it up? Help them by asking for more or less of either where it will help them most.

3) Do you agree with their ultimate argument about what their ethnographic project means? If so, what in the piece is convincing? What could be more convincing? If not, why not? What do you think they are missing--or where are they making a connection that might not be there?

4) If they were to continue on with this project, what recommendtions would you have for them? What might they do to extend it? What kinds of reading/research could they do to augment the work they have here?

A few things: First, I failed to mention that the profile page with excerpts and links to your literacy histories have been available since last week. Meant to say that in class. I'm hoping to do a modest assignment with them in tonight's class, but am not sure we'll have time.

Second: Peyton and Sara have the floor tonight for their presentation. I opted to have that serve as our presentation over rhetoric and argumentation, but I will spend some time talking about that connection in class.

Third: For our workshop tonight, I'm hoping that folks can get more than one reader, so I've set up groups in a weird pattern of three so everyone has two readers. I know that the syllabus is confusing, but, essentially, I don't think we'll have time for folks to get all the feedback to each other that might be useful, so I'm hoping that folks will take the time to respond completely over the next few days. I say midnight on the day of class, but that's not realistic when we end nearly at 9:00. Perhaps get feedback to folks by Friday of this week, giving folks the weekend to get things done.

Sara: Dawna & Kasey

Kasey: Cassie & Peyton

Peyton: Nick & Devon

Devon: Peyton & Nick

Nick: Kasey & Cassie

Cassie: Sara & Dawna

Dawna: Sara & Devon

Lastly, last week most folks did not have any kind of a reading journal and the week before that, not many people had posted to our discussion board. Please try to catch up with that material as soon as you can. I am not very demanding about these things, but I do keep a record of these things and the last two weeks have some holes in them for many folks.

Questions for Tuesday night's workshop (I'll most likely cut and paste these into the comments--but if you need them for later for your own paper or one of the two papers you are reading):

1) What are your takeaways from reading their observations--are there things that you notice that your writer did not? Tell them. Tell them why they are interesting and how they might fit into the overall analysis?

2 Is the balance of analysis to observation appropriate? If not, where are they erring--too much observation and not enough of what it means? Too much analysis without enough observation to back it up? Help them by asking for more or less of either where it will help them most.

3) Do you agree with their ultimate argument about what their ethnographic project means? If so, what in the piece is convincing? What could be more convincing? If not, why not? What do you think they are missing--or where are they making a connection that might not be there?

4) If they were to continue on with this project, what recommendtions would you have for them? What might they do to extend it? What kinds of reading/research could they do to augment the work they have here?

27 February 2024

Questions We Want Answered from Antiracist Writing Assessment:

20 February 2024 (a quick recap)

Ahead of today’s class, I want to circle back to some important highlights from the past two weeks of reading. I think it's useful given the snowday last week. It’s my hope that you will see the a picture of the discipline from a theoretical, historical, and practical point of view:

To support your understanding of the readings and the field, I’m including below short summaries of each of the readings so far. Pay particular attention to the Wardle/Adler-Kasner material. I know that that stuff is hard, but it’s important that we don’t allow the personal to overshadow the theoretical and rhetorical because it is less easy to process.

Irene Clark is providing a summary of what we have come to understand as “process pedagogy”. She identifies the when process comes on the scene it challenged how writing was taught prior. She explores key-concepts in process But she also challenges the ways that process has become as lock-step as any other kind of previous pedagogy and how the field has moved away from process to “post-process”: The linear model of prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing has come to dominate writing instruction, particularly at the K-12 level. She looks at key influences including the developing and renewed interest in rhetoric in the field of composition as it connects to the writing process, the role of cognitive psychology in the 80s, Social Constructivism and it’s influence on collaborative learning–all things that feel very familiar and central to anyone who has been in writing classroom as a teacher or a student for the past probably 50 years.

The "Guide to Composition Pedagogy," edited by Tate, Rupiper, and Schick, provides a bibliographic essay on two influential approaches in composition studies written by two important scholars of Process and Expressivism. Process pedagogy emphasizes the fluid and recursive nature of the writing process, rejecting the idea of writing as a linear series of steps (connects with Clark). It also emphasizes the importance of invention and discovery in writing, encouraging students to explore their ideas through writing. In that way, there is considerable overlap with Expressivist pedagogy, on the other hand, which focuses on personal expression and self-discovery through writing. This approach emphasizes the importance of students' voices and experiences, encouraging them to write authentically and explore their thoughts and feelings. Expressivist pedagogy also values the process of writing over the final product, emphasizing the journey of self-discovery and personal growth that writing can facilitate. You can understand these two movements, early ones in the field as a reaction and then you can understand “Why Johnny” as a reaction to that reaction–the emphasis on the personal, the movement away from prescriptivism, the valuing of student ideas and voices over the literary.

Wardle and Adler-Kassner's Concept 1, "Writing is a Social and Rhetorical Activity," emphasizes that writing is not merely a solitary act of transferring thoughts onto paper but is deeply connected to social contexts and rhetorical situations. They argue that writing is shaped by various social factors, including audience, purpose, and genre, and that understanding these factors is essential for effective writing instruction. You can see here how this moves away from the expressivist pedagogies. It’s much less about the individual and more about the collective. One key aspect of this concept is the idea of "rhetorical awareness," which involves understanding how different rhetorical choices can impact the reception of a piece of writing. This includes understanding the expectations and conventions of different genres and discourse communities. In that way, it kind of right sizes what process and expressivism get wrong–which is the lack of thinking about our writing in the world (hard in the classroom, but important). Connected: Wardle and Adler-Kassner also highlight the importance of considering the social implications of writing, such as how writing can be used to advocate for social change or perpetuate harmful stereotypes.

Sharon Crowley's "Composition in the University: Historical and Polemical Essays" begins with a critical examination of the historical development of composition studies. She argues that the field has been shaped by conflicting ideologies, including the tension between a skills-based, utilitarian approach to writing and a more humanistic, expressive view. Crowley contends that this tension has led to a lack of coherence in composition studies, with scholars often unable to agree on the goals and methods of the field. One of Crowley's key critiques is the marginalization of composition within the university, both in terms of its status as a discipline and its role in shaping students' intellectual development. She argues that composition is often seen as a remedial, lower-level course, rather than a central component of a student's education. This marginalization, she suggests, is due in part to the field's association with teaching rather than research.

Kathryn Fitzgerald's "A Rediscovered Tradition: European Pedagogy and Composition in Nineteenth Century Midwestern Normal Schools" explores the influence of European pedagogical practices on composition instruction in Midwestern normal schools during the 19th century. Fitzgerald argues that these normal schools played a crucial role in shaping composition pedagogy in the United States, drawing on European models of rhetorical education. One of the key strengths of Fitzgerald's work is its focus on a lesser-known aspect of composition history, shedding light on the often-overlooked influence of European pedagogy on American education.We don’t need to look to the Midwest to understand this. BSU is the third oldest normal school in the country. Here we see this historic connection between composition studies and K-12 education–which has always been and will continue to be a tension in the field.

Asao Inoue's "Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future" challenges traditional approaches to writing assessment, advocating for a shift towards antiracist practices in education. In the introduction, Inoue argues that traditional assessment methods are inherently biased, often privileging certain groups while disadvantaging others. He suggests that these biases are deeply rooted in our societal structures and that they manifest in writing assessment through standards that are implicitly based on white, middle-class norms. So here we can see several ideas all at once: the critique of process and expressivism as being about privilege–you are privileged if someone is saying that what you are writing is in and of itself of value and important. That can be a good thing, but it can also be a bad thing. And we see how Wardle/Adler-Kasner’s idea about the social implications of writing are embedded in how we teach writing. Inoue proposes a radical rethinking of writing assessment, one that focuses on fostering equitable learning environments. He introduces the concept of "writing assessment ecologies," which considers the complex interactions between students, teachers, assessments, and contexts. This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding students as individuals with diverse backgrounds and experiences. Critics of Inoue's work argue that his approach is too idealistic and impractical for widespread implementation.

Questions We Want Answered from Antiracist Writing Assessment:

- What does “antiracist assessment” look like in an actual classroom?

- What does “sustainability” look like to him?

- How do you antiracist grade an assignment?

- How do you encourage other teachers to try antiracist assessments?

- Do you think teachers who have taught in the current system/structures can/would be willing to learn this other way?

- What should we do to reframe our ideas about good/antiracist writing practices

- Where is the resistance to race and racism? And why do you think it happens?

- What skills should we prioritize our students having when leaving our classrooms?

- What do students think about these antiracist ecologies?

- How do we create these sustainable places for living and learning?

20 February 2024 (a quick recap)

Ahead of today’s class, I want to circle back to some important highlights from the past two weeks of reading. I think it's useful given the snowday last week. It’s my hope that you will see the a picture of the discipline from a theoretical, historical, and practical point of view:

- The field of Composition happens at the intersection of major historical moments at the of democratic change and growth (The GI Bill, Open Admissions, Civil Rights, The Women’s Movement, Black Lives Matter).

- The field of Composition has historically been marginalized in English Departments as a lesser form of study and scholarship–partially because it values student writing and the writing process of all writers rather than the creative writing process of elite producers (literary text production) (see Crowley in particular for this)

- The field of Composition is not one history, but many histories, of literacy instruction in the US (see Crowley and Fitzgerald in particular, think about BSU’s own history)

- The field of Composition has evolved theoretically and continues to think and rethink what the act of writing involves–how writing is done, what role it plays in the personal, what role it plays in the public (think about starting with Clark, what we read in Guide to Composition Pedagogies on Process and Expressivist Pedagogies, think about Inoue).

To support your understanding of the readings and the field, I’m including below short summaries of each of the readings so far. Pay particular attention to the Wardle/Adler-Kasner material. I know that that stuff is hard, but it’s important that we don’t allow the personal to overshadow the theoretical and rhetorical because it is less easy to process.

Irene Clark is providing a summary of what we have come to understand as “process pedagogy”. She identifies the when process comes on the scene it challenged how writing was taught prior. She explores key-concepts in process But she also challenges the ways that process has become as lock-step as any other kind of previous pedagogy and how the field has moved away from process to “post-process”: The linear model of prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing has come to dominate writing instruction, particularly at the K-12 level. She looks at key influences including the developing and renewed interest in rhetoric in the field of composition as it connects to the writing process, the role of cognitive psychology in the 80s, Social Constructivism and it’s influence on collaborative learning–all things that feel very familiar and central to anyone who has been in writing classroom as a teacher or a student for the past probably 50 years.

The "Guide to Composition Pedagogy," edited by Tate, Rupiper, and Schick, provides a bibliographic essay on two influential approaches in composition studies written by two important scholars of Process and Expressivism. Process pedagogy emphasizes the fluid and recursive nature of the writing process, rejecting the idea of writing as a linear series of steps (connects with Clark). It also emphasizes the importance of invention and discovery in writing, encouraging students to explore their ideas through writing. In that way, there is considerable overlap with Expressivist pedagogy, on the other hand, which focuses on personal expression and self-discovery through writing. This approach emphasizes the importance of students' voices and experiences, encouraging them to write authentically and explore their thoughts and feelings. Expressivist pedagogy also values the process of writing over the final product, emphasizing the journey of self-discovery and personal growth that writing can facilitate. You can understand these two movements, early ones in the field as a reaction and then you can understand “Why Johnny” as a reaction to that reaction–the emphasis on the personal, the movement away from prescriptivism, the valuing of student ideas and voices over the literary.

Wardle and Adler-Kassner's Concept 1, "Writing is a Social and Rhetorical Activity," emphasizes that writing is not merely a solitary act of transferring thoughts onto paper but is deeply connected to social contexts and rhetorical situations. They argue that writing is shaped by various social factors, including audience, purpose, and genre, and that understanding these factors is essential for effective writing instruction. You can see here how this moves away from the expressivist pedagogies. It’s much less about the individual and more about the collective. One key aspect of this concept is the idea of "rhetorical awareness," which involves understanding how different rhetorical choices can impact the reception of a piece of writing. This includes understanding the expectations and conventions of different genres and discourse communities. In that way, it kind of right sizes what process and expressivism get wrong–which is the lack of thinking about our writing in the world (hard in the classroom, but important). Connected: Wardle and Adler-Kassner also highlight the importance of considering the social implications of writing, such as how writing can be used to advocate for social change or perpetuate harmful stereotypes.

Sharon Crowley's "Composition in the University: Historical and Polemical Essays" begins with a critical examination of the historical development of composition studies. She argues that the field has been shaped by conflicting ideologies, including the tension between a skills-based, utilitarian approach to writing and a more humanistic, expressive view. Crowley contends that this tension has led to a lack of coherence in composition studies, with scholars often unable to agree on the goals and methods of the field. One of Crowley's key critiques is the marginalization of composition within the university, both in terms of its status as a discipline and its role in shaping students' intellectual development. She argues that composition is often seen as a remedial, lower-level course, rather than a central component of a student's education. This marginalization, she suggests, is due in part to the field's association with teaching rather than research.

Kathryn Fitzgerald's "A Rediscovered Tradition: European Pedagogy and Composition in Nineteenth Century Midwestern Normal Schools" explores the influence of European pedagogical practices on composition instruction in Midwestern normal schools during the 19th century. Fitzgerald argues that these normal schools played a crucial role in shaping composition pedagogy in the United States, drawing on European models of rhetorical education. One of the key strengths of Fitzgerald's work is its focus on a lesser-known aspect of composition history, shedding light on the often-overlooked influence of European pedagogy on American education.We don’t need to look to the Midwest to understand this. BSU is the third oldest normal school in the country. Here we see this historic connection between composition studies and K-12 education–which has always been and will continue to be a tension in the field.

Asao Inoue's "Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future" challenges traditional approaches to writing assessment, advocating for a shift towards antiracist practices in education. In the introduction, Inoue argues that traditional assessment methods are inherently biased, often privileging certain groups while disadvantaging others. He suggests that these biases are deeply rooted in our societal structures and that they manifest in writing assessment through standards that are implicitly based on white, middle-class norms. So here we can see several ideas all at once: the critique of process and expressivism as being about privilege–you are privileged if someone is saying that what you are writing is in and of itself of value and important. That can be a good thing, but it can also be a bad thing. And we see how Wardle/Adler-Kasner’s idea about the social implications of writing are embedded in how we teach writing. Inoue proposes a radical rethinking of writing assessment, one that focuses on fostering equitable learning environments. He introduces the concept of "writing assessment ecologies," which considers the complex interactions between students, teachers, assessments, and contexts. This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding students as individuals with diverse backgrounds and experiences. Critics of Inoue's work argue that his approach is too idealistic and impractical for widespread implementation.

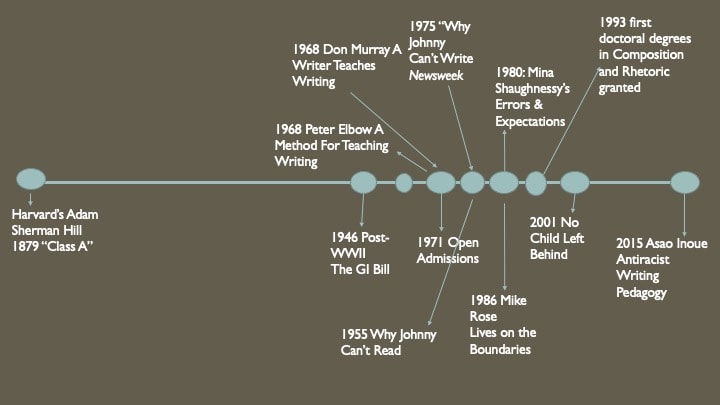

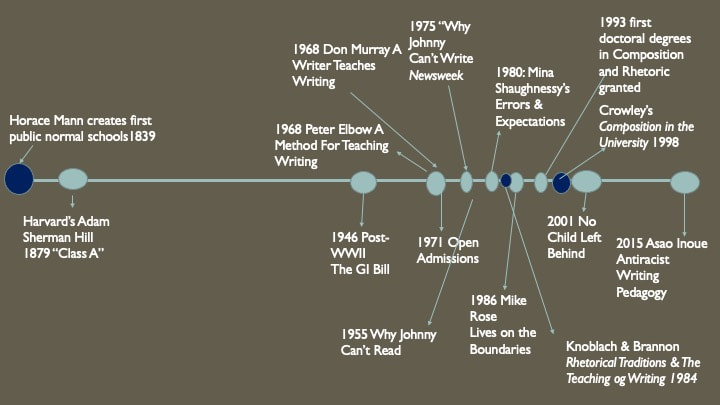

13 February 2023 A Brief Timeline

Not everything on the two timelines below are going to make sense at this moment, but as we continue with the semester I think it will become clearer what this means. The first version of this timeline tries to show Process Pedagogy situated historically and in the field. The second one inputs moments that diverge from the traditional telling of the history of the field (Crowley's critique and where Normal Schools fit in).

Not everything on the two timelines below are going to make sense at this moment, but as we continue with the semester I think it will become clearer what this means. The first version of this timeline tries to show Process Pedagogy situated historically and in the field. The second one inputs moments that diverge from the traditional telling of the history of the field (Crowley's critique and where Normal Schools fit in).